Comics : “I used my elbow to hit this guy and escape !” (1/2)

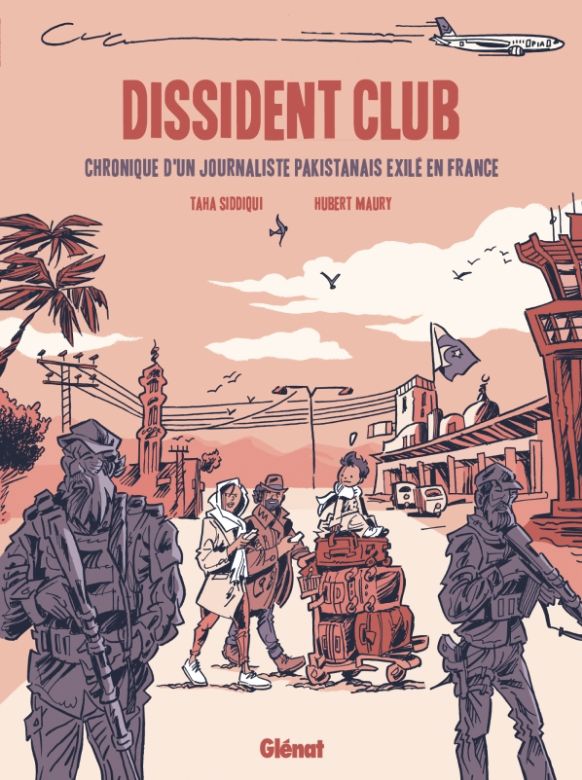

From Brussels to Paris, going to meet Pakistani exiled journalist Taha Siddiqui who is the author of an autobiography comic-book-style named "Dissident Club".

I went to the beautiful city of Paris in France, approximately 350 km from Brussels, to meet Taha Siddiqui a reporter/journalist who has published a comic-book-style autobiography and owns a coffee bar named « Dissident Club ».

The journey involved a 5-minute walk to reach the appointed location. As I approached the area, an alley occupied by African shops caught my attention. This scene reminded me of the alley called Meh Tangi in Chaussee de Ixelles, Brussels. When I identified the club’s sign, I thought to myself, « Here I am » and confidently went in.

Entering the club at 7 o’clock in the evening, I found several people engaged in conversations and sipping drinks at the bar. In one corner stood a man around 175 cm tall, with black hair, black eyes, and a beard. He wore a smile on his face. I approached him and asked if he was Taha Siddiqui, adding with a laugh, « If you were waiting for me, here I am. I’m from Brussels! »

« Yes, the Afghanistani reporter from Latitudes ! »

His own laughter accompanied his confirmation, « Yes, the Afghanistani reporter from Latitudes ! «

Seating ourselves on a corner sofa, we started our conversation. The interior of the place was adorned with photographs of world leaders, paintings, cartoons, books on shelves, and a few handicrafts serving as souvenirs. Hints of Pakistan were also visible in the decor.

Taha Siddiqui was born into a deeply religious family in Islamabad, Pakistan. He spent his formative years in Saudi Arabia, where he completed his high school education. With two brothers and a sister, his family lived between Saudi Arabia and Pakistan.

As an investigative journalist

Upon returning to Pakistan at the age of 17, Siddiqui pursued training in journalism, a profession that ignited his passion. From then on, he maintained connections with the global press, enjoying more freedom than he experienced in Saudi Arabia. His passion and interest led him to work as an investigative journalist, and his investigations focused on uncovering significant matters, particularly the opaque workings of the military, which are often inaccessible to the Pakistani public.

Several years ago, Siddiqui worked as a reporter for diverse international media outlets in Pakistan, gaining recognition as an investigative journalist from governmental bodies, the military, and politicians alike.

Currently, in exile in France, Siddiqui recounted, « I left my homeland in January 2018 after surviving an assassination attempt and kidnapping by armed men on my way to Islamabad airport during my investigative endeavours related to the military sector. »

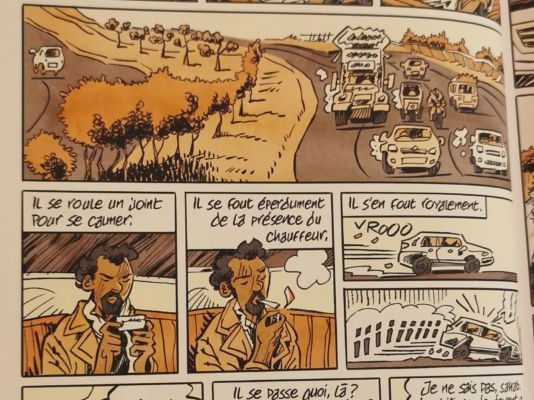

He believes that the orchestrated nature of his kidnapping pointed to the military as the perpetrators due to the potential threat he posed to their interests. Describing the traumatic experience, he told how he was apprehended and later managed to escape. It was the morning of 10 January 2018, when unknown armed men halted his taxi en route to the airport.

He was forced into another vehicle, bound with handcuffs. Reflecting on the harrowing experience, he said, « I was bewildered for a few moments, struggling to fathom the gravity of the situation. » In a moment of relative calm, he noticed an unlocked door within the vehicle, which became his means of escape.

With a sad expression, Siddiqui talked about the day of his kidnapping. The man held a gun to his stomach and ordered him to get into the other car, and they put handcuffs on him. “And I said to the guys, I’m going with you but why are you holding me like a criminal? Let’s go. I’m relaxed and calm, but don’t shoot on me.”

Summoning up his courage, he used his elbow to subdue one of his captors and leaped from the moving car, sprinting into a nearby street. Despite threats to halt or be shot, he evaded capture and concealed himself in another alleyway.

“I was lost for a few minutes.”

To be kidnapped and not know what is happening to you and your family! “I was lost for a few minutes : I can’t describe how difficult it was. However, when they calmed down and relaxed a little bit, it was my opportunity to see that no one was sitting on the right side of me.”

Subsequently, Siddiqui held a press conference to shed light on his ordeal, implicating the Pakistani military. He received numerous death threats from diverse sources, including the interior ministry. They demanded he retract his statements from the media. Remaining steadfast, he refused to acquiesce.

The interior minister of Pakistan approached him, declaring, « The government has no issue with you, but the military does. You should apologize to the military and remain silent. » Baffled by the request, Siddiqui challenged the notion, reasoning that the head of the ministry should command the military, not the other way around. This incident cemented his resolve to flee Pakistan.

His subsequent roles included serving as a correspondent for France 24TV in France, contributing to the New York Times, and reporting for the Guardian. Most of his work was for Western media, encompassing both print and television outlets.

Siddiqui held the conviction that he became a target due to his criticism of the Pakistani military, particularly his investigations into clandestine prisons for the New York Times.

A key element of his work was highlighting the far reaching influence of the Pakistani military. The main topic of his coverage was to talk about the Pakistani military, which is powerful in all sorts of areas. Its influence extends to business, it has connections in government, and it is active in different political sectors. It is responsible for manipulation everywhere.

« I refusing to remain silent. »

He was reporting and investigating all that, as well as reporting on human rights issues.

A half-decade before the attempt on his life, he frequently suffered pressure to silence his inquiries. He recalled, « They urged me to cease my investigations. I resisted their attempts to muzzle me, refusing to remain silent. »

A « kill liste »

His journalism encompasses human rights and other topics. Deciding to leave Pakistan, he pondered the cases of missing individuals that plagued the country after his departure. Ultimately, he embarked on a journey into exile in France with his wife and four-and-a-half year old son, successfully navigating the challenges of relocation.

Currently residing in Paris, Siddiqui and his family endure a sense of insecurity. Unidentified callers and intrusive visitors to his workplace compound this unease. Nevertheless, he perseveres in his work, determined to continue his professional pursuits. In January 2018, French authorities cautioned him against travelling to Pakistan, revealing that his name was included on a ‘kill list’.