Israel-Iran War: Strasbourg at Christmas, the Middle East in shadow (3/3)

Among the New Year’s lights in Strasbourg, how a chance encounter between a journalist and an Israeli–French medical student reveals a clearer picture of the silent reality of war. A narrative of the growing rift between politics and people amid the wars of the Middle East.

When I travelled to Strasbourg to cover the monthly session of the European Union Parliament, where representatives of European countries vote on matters previously discussed in Brussels, and in doing so approve or reject various pieces of legislation I expected my days to be filled with political analyses, formal interviews, legal debates, and the tense atmosphere of European politics.

But what has occupied my mind ever since was not the heated discussions inside the Parliament, but a brief conversation that took place amid the colourful lights of the city’s Christmas market. It was a conversation that revealed another dimension of the Middle East’s wars, one that politicians often ignore but ordinary people, the very ones who bear the true cost of war, experience with their lives and emotions.

In the final days of the year, Strasbourg looks like a dreamy scene from a winter film. The city’s old streets, decorated with artistically arranged lights, glow with an enchanting brilliance. The Christmas markets, filled with the aroma of cinnamon, hot drinks, local pastries, and handicraft stalls, bring the spirit of warmth and festivity to its peak. Thousands of tourists from various countries, families, and young people stroll through this atmosphere under intense security measures, transforming the city for several weeks into the beating heart of Europe’s winter celebrations.

But within this warm and human environment, I found myself face-to-face with the coldest issues burning through the contemporary world: war, rigid political strategies, and the widening gap between governments and the people.

At the foot of the Notre-Dame Cathedral

After covering consecutive meetings and a long workday, I decided to take a short walk in the damp evening air and enjoy the festive mood. Next to the magnificent Notre-Dame Cathedral, I asked two young men to take a photo of me. It was one of those moments that usually seems insignificant but sometimes becomes the beginning of a profound conversation.

As the young man took photos with great care, I asked if he was a photographer. He laughed and said no, but whatever he did, he liked to do it properly. I introduced myself as Lilo, a journalist who had come from Brussels, and said that Strasbourg becomes extraordinarily beautiful at the year’s end.

Then I asked his name. He introduced himself as Gabriel, a medical student and resident of Strasbourg. After a few short exchanges, when I learned he was Israeli French, I felt encouraged to continue the conversation and asked him an important question: what was his opinion about the recent war between Iran and Israel?

His response may surprise many readers, for it stood in sharp contrast to the official narratives that dominate global media coverage.

“This war is not the war of the Israeli people, it is Netanyahu’s war.”

The young student said without hesitation, “this war is Netanyahu’s war. Not the war of the Israeli people. And not the war of the Iranians. He is the one who has trapped millions inside and outside Israel, and he refuses to end the war because doing so would threaten his grip on power.”

These words, coming from a young man born in France but with Israeli roots, are striking. He was neither a political activist nor affiliated with any group, just a citizen who thought freely enough to criticise Israel’s official narrative.

He continued: “If Netanyahu loses power, he will very likely face legal prosecution. That is why war is a political tool for him, not a security necessity. It is a bitter reality that the fate of people becomes tied to the decisions of an individual who sees his survival in the continuation of the crisis.”

In his eyes, there was something that is absent in the eyes of politicians: the real pain of human beings.

Through the eyes of Europe’s young generation

More striking than his criticism was the perspective he shared with the people of Iran. He said: “My best friend is an Iranian girl who lives in this city. We feel no hostility toward each other. The people of Iran and Israel have no problem with one another. The problem lies with the politicians, not the citizens.”

This sentence reflects a truth often lost in the noise of the media: in many free societies, members of the younger generation increasingly ignore artificial identity boundaries. They no longer believe in military narratives or political hero-making. They believe more in peace, friendship, and coexistence.

Interestingly, he said that during the 12-day Iran-Israel war, many Iranians and Israelis across different countries stood side by side, took photos together, published joint messages of peace, and declared that they were not enemies. This reality is seldom reflected in the official media of either side.

“We have no time for war making. We must spend our energy saving the planet, not destroying human lives.”

At the end of our conversation, the young student said something that showed his mindset was not merely emotional, but realistic and responsible: “Our world is already struggling with crises like climate change. We have no time for war-making. We must spend our energy saving the planet, not destroying human lives.”

This statement highlights a key point: while political leaders remain absorbed in displays of power, the younger generation is concerned about humanity’s real problems problems that may endanger life on Earth in the coming decades.

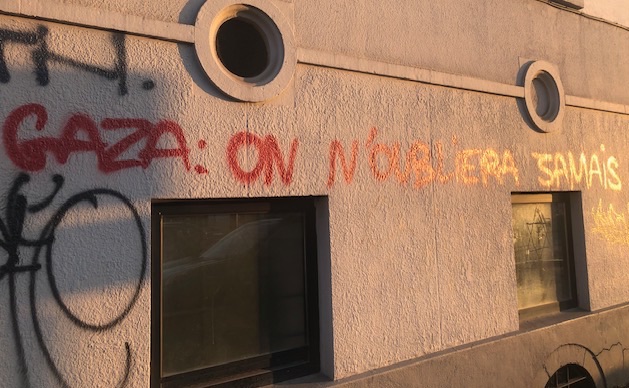

Echoes of protest in the heart of Europe

After the ceasefire, I attended various demonstrations across European cities as a journalist. What was common among all these gatherings was a clear, firm demand: “No to war”.

From Brussels to Berlin, from Paris to Amsterdam, the voices of people beyond geography and politics carried a single message: war is neither a solution nor even an option.

“We only want to live in peace. We want to see our families safe, not hear news of death every day.”

In one of these gatherings near the famous Grand-Place in Brussels, I had spoken earlier with Nasrin, an Iranian-European woman. With a trembling voice full of emotion, she said, “How long must innocent people pay the price for the decisions of leaders? How many more cities must be destroyed? How many more families must be displaced before the world wakes up?”

A fierce opponent of war, she continued, “we only want to live in peace. We want to see our families safe, not hear news of death every day.”

Nasrin was not alone. Dozens around her held placards supporting the people of Iran and Palestine. Notably, they did not support only one side of the war, they supported all its victims, regardless of nationality.

This is what politicians often fail to grasp: people rarely disagree over humanity.

Between people and interests

In many of these demonstrations, Europeans openly criticised world leaders, including the governments of the United States, Russia, and Israel. They saw unilateral, threatening, and interventionist policies as drivers of continued conflict.

Many believed governments should allow every nation to determine its political path and future without interference from extremist leaders or foreign powers. These protests illustrate a deepening divide between politics and the people.

My conversation with the young student in Strasbourg is a small example of a larger reality: in today’s wars, people often understand and articulate the truth more clearly than governments do.

Leaders speak of “national interests”, but young people speak of “human interests”. Governments emphasise “security” , but people emphasise “life”. Politicians think of “victory” , but people think of “survival”.

In the contrast between a simple photo request in a Christmas market and a complex conflict in the Middle East lies an invisible yet undeniable connection: even far from the battlefield, people are not spared from the effects of war-driven politics.

Peace begins with small conversations

As I walked away from that conversation, under the colourful glow of the Christmas market lights, I thought that perhaps great peace efforts do not begin at the tables of world leaders, but in small, simple conversations like this one: where two strangers with different backgrounds speak about shared human pain, where people, despite cultural and political differences, understand that they are not each other’s enemies.

Now, as the world approaches the year 2026, perhaps the greatest message from that brief encounter is this: people around the world want peace more than ever, and perhaps it is time for politicians to finally listen.