Is peace possible in Turkey ?

Turkey has faced the Kurdish issue many times in the 102 year history of the republic. Now, however, a new possibility for peace is being discussed. In the 41-year conflict between Turkey and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), thousands of people have lost their lives, tens of thousands have been displaced, and thousands of settlements have been destroyed. We spoke to a member of parliament from the DEM Party (representing Kocaeli), an exiled journalist, an academic, and a representative of a Kurdish association in Belgium, and asked : 'Is peace possible in Turkey ?’

The Republic of Türkiye, founded in 1923, adopted a unitary state structure. As the Ottoman Empire’s multi-ethnic and multi-religious structure collapsed, Armenians, Assyrians, Greeks, and other non-Muslim minorities were either subjected to forced migration or became targets of mass violence.

When the republic was established, the Kurds were the second largest ethnic group after the Turks. In Turkish Kurdistan (in southeastern Turkey), this majority people’s language was banned, and their identity was not constitutionally recognised. Article 3 of the Turkish Constitution states: « The Turkish state, its territory, and its nation are indivisible. Its language is Turkish… » Article 66 states « everyone who is bound to the Turkish state by citizenship is a Turk. » Article 4 explicitly states that the first three articles of the constitution are unchangeable.

Between 1923 and 1938, Kurdish uprisings against the republic were suppressed. From 1939 to 1984, Kurdish political organisations were fragmented. Their identity, language, and cultural rights were not recognised. In this repressive environment the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party), founded in 1978 by a group of university students in the Fis village of Lice, Diyarbakır, was established with the goal of an independent Kurdistan. It carried out its first armed action on 15 August 1984, in the Kurdish-populated districts of Eruh, Siirt, and Şemdinli, Hakkari. Since that day, in armed conflicts that have occasionally been interrupted by ceasefires, more than 40.000 people have lost their lives.

Ten years after the collapse

The last major peace initiative, the 2013-2015 solution process, ended when the talks collapsed. Now, ten years after that collapse, the possibility of peace in Turkey is back on the table. On 27 February 2025, Abdullah Öcalan, the founding leader of the PKK, who has been held in the İmralı prison since 1999, made a call for ‘Peace and a Democratic Society’ through members of parliament from the Peoples’ Equality and Democracy Party (DEM Party), stating that « all groups should lay down their arms and PKK should disband. »

The call included the statement: « Solutions like separate nation-states, federations, administrative autonomy, and culturalist approaches, which are the inevitable result of extreme nationalism, do not provide a response to historical social sociology. »

After the text was shared with the public, DEM Party MP Sırrı Süreyya Önder- who passed away on 3 May- also conveyed a verbal message from Öcalan: « While presenting this perspective, it is certain that in practice, laying down arms and disbanding the PKK would require the recognition of democratic politics and legal aspects. »

Following the release of the statement, the PKK declared a ceasefire on 1 March and, on 12 May, announced that it had laid down its arms and formally dissolved itself. In the congress where the dissolution was decided, the PKK emphasised that the Kurdish issue should be addressed in parliament and called on international actors to contribute constructively to the peace process.

Tuncer Bakırhan, co-chair of the DEM Party, stated that they support the process and emphasised that the first step should be improving Öcalan’s living conditions and allowing him to meet with the public.

The Kurdish issue in parliament

Devlet Bahçeli, leader of the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), also supported resolving the Kurdish issue in parliament. However, in his statement -‘How and to what extent the potential transition and transfer from the dissolved PKK to the PYD (Democratic Union Party) and YPG (People’s Protection Units) will be monitored and coordinated simultaneously…’ – he differentiated the PKK from the YPG, which controls northern and eastern Syria and is predominantly Kurdish.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, on the other hand, stated that in addition to the PKK, the YPG must either disarm or be integrated into the Syrian Army.

In this new peace process – supported by nearly all political parties in Turkey – the PKK has laid down its arms, and there are calls for the issue to be discussed unconditionally in the parliament. But the key question remains: will a new constitution be drafted that grants Kurds their identity and language rights in Turkey, or will history simply repeat itself?

So, is societal peace possible in Turkey 102 years on?

« I believe Bahçeli has become the real driver of this process. »

Ömer Faruk Gergerlioğlu, human rights defender and Member of Parliament for the DEM Party, representing Kocaeli, highlights the unexpected start of the current peace process. He recalls that, in October 2024, the moment when MHP leader Devlet Bahçeli greeted DEM Party MPs on the floor of the Turkish Grand National Assembly was a surprise even for them. For Gergerlioğlu, this gesture signalled the beginning of a new process: “I believe Bahçeli has become the real driver of this process, and Erdoğan accepted his coalition partner’s political line. Bahçeli perceives a threat to the survival of the state. This process should not be interpreted through the lens of a new constitution or potential early elections, but rather through the changing dynamics in the Middle East.”

A buffer force

According to Gergerlioğlu, the Israeli assault on Gaza on 7 October 2024, and the subsequent fall of the Damascus regime, significantly altered the balance of power in Syria. As the Syrian government collapsed, Turkey and Israel, he notes, effectively became neighbours : “In this new geopolitical equation, Ankara saw an opportunity to prevent the Kurds from collaborating with Israel. Kurds may be seen as a potential ‘buffer’ force between Turkey and Israel.”

« Even a softening of the hardline security policies could pave the way for future positive developments.”

Gergerlioğlu links Bahçeli’s signals regarding possible legal and constitutional steps to this regional realignment, arguing that these gestures are driven by strategic calculations rather than human rights concerns. He believes that Öcalan also recognised this political opportunity and re-entered the peace process. While not expecting a full resolution, he thinks partial rights could be granted, and that the state’s long-standing policy of marginalising Kurdish identity might be revised : “I don’t expect sweeping democratic reforms. But even a softening of the hardline security policies could pave the way for future positive developments.”

Gergerlioğlu also suggests that the state may have provided Öcalan with certain assurances. He notes that Turkey likely wants the YPG in Syria to be transformed into a controlled force through integration into the Syrian Army. He concludes with a clear message : “Armed conflict has benefited neither Kurds nor Turks. So far, this peace process has progressed positively. With genuine steps from the state, the Kurdish question could finally become a topic of open political discussion. “

From equality to one-sidedness

According to academic Yektan Türkyılmaz, Erdoğan’s intention is not so much peace as it is to control the Kurdish movement in line with his political goals. Türkyılmaz points out that the current solution process is very different from the version in 2007: « At that time, there was a table in Oslo where both sides sat equally, with international hosts and mediators. Now, on one side, there is the imprisoned Öcalan, and on the other, free state officials ».

Moreover according to Türkyılmaz, this process is « sui generis », a model with no precedent in the world. He also argues that one of Erdoğan’s primary objectives is to fracture the emerging opposition bloc between the Republican People’s Party (CHP) and the DEM Party.

Türkyılmaz also stated : “The process is being carried out in a rushed and overly rigid manner. Yet such transformations require a solid social, legal, and economic foundation. Otherwise, as in the past, the PKK could reemerge under a different name and structure.“

Highlighting the shifting regional dynamics, Türkyılmaz noted that after Iran’s influence weakened in Damascus, a power struggle has emerged between Israel and Turkey. He explained that Turkey is now seeking to reduce risks and capitalise on opportunities by reestablishing ‘relations’ with the YPG, similar to its approach in 2012.

“Peace is possible through mutual steps.”

Lastly, Türkyılmaz states that while the Kurdish people are ready for peace, if their political demands are not met, support for the process will weaken : « Peace is possible through mutual steps. Moreover, this will not only positively affect Turkey’s internal peace but also its relations with the EU. However, I do not believe that this process will reach a conclusion in its current form. »

Hopeful and apprehensive

Orhan Kılıç, the head of external relations at The Belgium Kurdish Society Center (Nav-Bel) Association, representing the Kurdish community in Belgium, says that the diaspora in Europe approaches the process with cautious optimism. Kılıç states that Öcalan’s call is supported, saying : « We want peace. But if the people’s demands are not met, the reaction will grow. The Kurdish people want freedom, not assimilation. »

Kılıç summarises the fundamental demands of the Kurds as follows : « Self-governance, education in the mother tongue, living their culture, and telling their history. »

He emphasises that the new constitution should recognise the Kurdish identity, arguing that strengthening local governance could create a real bond between the people and the state.

« However, peace is made with the enemy. We will sit and talk with those who killed us as well. »

Expressing concerns that Erdoğan may use the process to further his aim of autocratisation, Kılıç adds : « However, peace is made with the enemy. We will sit and talk with those who killed us as well, » stressing the importance of supporting the process.

Kılıç underscores that the Kurdish people want peace, and if this process succeeds, there are also those in the Kurdish diaspora in Europe who wish to return to Turkey.

Legal steps for true peace

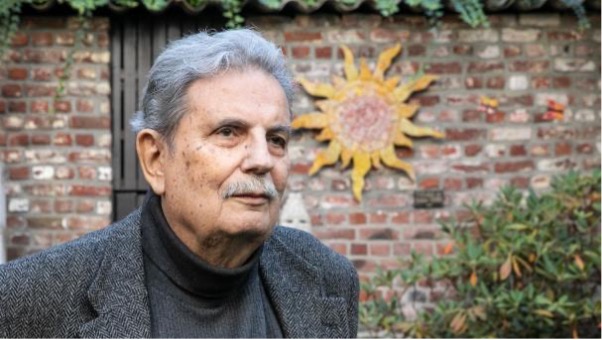

After stating that both Öcalan and the PKK have called for “legal and democratic reforms,” experienced journalist Doğan Özgüden emphasised that the AKP-MHP government could create an environment conducive to genuine peace by releasing Öcalan, former HDP leader Selahattin Demirtaş and his colleagues, Osman Kavala and the Gezi Park protest detainees, as well as Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu.

After emphasising that legal reforms and democratision are essential for peace, Özgüden stated : “The refusal of the YPG to disarm, in the face of almost universal international support for Ahmed al-Shara, the leader of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham which controls the Syrian administration, is a completely legitimate right of the people of Rojava. The Ankara regime and its supporters will be solely responsible if a new cycle of conflict begins. Furthermore, unless the call made by the Kurdistan National Congress (KNK), held on 24-25 May in the Netherlands with delegates from the four parts of Kurdistan and the diaspora, is taken into account, it will not be possible to end the conflict.”

Özgüden concluded by stating, « one of the main conditions for ending the current regime in Turkey is the resolution of the Kurdish issue. »

A new threshold for peace or an old cycle ?

The Kurdish issue in Turkey is not merely a security problem; it has persisted for over a century as a matter of identity, equal citizenship, and democracy. Although the PKK’s decision to disband marks an important turning point, the current process raises various questions in the public sphere. There is no equality at the negotiating table; no discussions are held on legal guarantees, democratic reforms, freedom of expression, or local governance demands.

On one side are Erdoğan’s possible political manoeuvres, and on the other, the fragile yet still strong peace demands of the Kurdish people. The process continues amid great uncertainty, but with hope. Statements by President Erdoğan and Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan that the PKK’s disarmament alone will not suffice, and that the YPG and Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) in Syria—who follow Öcalan’s ideology—must also disarm, can be seen as the biggest obstacle to the process.

The unique dynamics of Syria suggest that YPG disarmament will be very difficult. If a new war does not erupt, the new state order in Syria will be decided by the US, Turkey, Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar. Since 2016, Bahçeli and Erdoğan, who have carried out heavy attacks against the Kurds in Turkey, Iraq, and Syria, are trying to draw the Kurds to their side by offering minimal rights while also taking advantage of the Kurds’ isolation on the international stage.

However, the PKK’s disarmament process presents an opportunity to improve the socio-economic rights of the Kurdish people. When supported by steps such as identity and cultural rights, economic development, increased educational opportunities, and job creation, this opportunity can strengthen Kurdish support for the peace process.

If Erdoğan abandons Neo-Ottoman policies and expansionist approaches, this new process—where the PKK has disarmed—could enable Turkey to become a democratic country again by improving the socio-economic and socio-cultural rights of Kurds and other oppressed communities.

On the other hand, the absence of observers and the secretive nature of the process increase the risks to achieving peace. It is clear that lasting peace requires not only unilateral calls but mutual steps, open negotiations, and constitutional guarantees.

Otherwise, history may repeat itself.